Newsletter #010: A Fatal Fear Of Football's Negligence To Head Trauma...

Ömer uses the 10th edition of Revamp The Game to remind us all of the ugly hidden truth in football. Head trauma, brain damage & death.

Despite Renewed Regulation…Do The Football Association (FA) Remain Negligent In Their Handling Of Head Injuries That Ultimately Lead To Long-Term Brain Damage In Professional Footballers?

Ömer Çayir

The Issue At Hand & The FA Guidelines

The issue of head injuries in football is becoming increasingly hard to ignore for those within the industry and is providing greater challenges for those responsible in senior sporting bodies. Many high profile cases regarding current and ex-professional footballers have resulted in a greater scrutiny on the negligent nature around football head injury and consequentially, questions are now starting to appear as to whether the regulations in football are satisfactory enough to protect the well-being of professional footballers.

This article will assess the very guidelines implemented by the Football Association (FA) and apply it to a theoretical negligence sequence established within tort law. There will be a specific focus on the duty of care owed by sporting bodies to their professional athletes with a primary focus on Watson v British boxing Board of Control 2000 and a critical analysis upon the standard and breach of duty. Moreover, I will take a deeper look into the material contribution and increase in risk tests, in which the definition of ‘industry’ is brought into question. A case such as Condon v Basi 1985 will provide useful legal reference points for the standard of care owed, and in highlighting the natural dangers that professional sport provides. Professional scientific opinion on the long-term effects of head trauma and concussion in sport with relevant examples of current and ex-professional cases will also be looked at. With the art of heading still an advocated part of the so called ‘beautiful game’, I will analyse whether this art will eventually expose the brutally ugly side of a game so universally loved.

The current FA Guidelines on heading: (Youth Level – Professional Level)

Youth Level:

· Under 6-11 level: Heading should not be used at this level in training sessions.

· Under 12 level: Heading should only occur once a month in training, with a maximum of 5 headers per session and a size 4 ball.

· Under 13 level: Heading should only occur once a week in training, with a maximum of 5 headers per session and a size 4 ball.

· Under 14-16 level: One session per week featuring a maximum of 10 headers with a size 5 ball.

· Under 18 level: No clear guidance other than heading should be reduced as much as possible in training.

Players between the ages of 11-18 are all exposed to repetitive head trauma from the impact of heading.

The significance of the youth regulation is that whilst it does not apply to professionals directly, it is the guidance that future professionals will have to follow. Hence, we should be made aware of the impact that heading creates not only during professional years but also during the build-up to a professional’s career. Now with the acceptance that heading occurs at youth level football, there is also an acceptance that teenage footballers are exposed to repetitive head trauma at a stage in which the myelination of the brain is yet complete. This is a biological process often completed at the age of 17…

Regarding the professional game, the guidance is as follows, following multiple studies undertaken by the Professional Football Negotiating and Consultative Committee (PFNCC):

· Due to the varying force involved in heading a football, the focus on the guidance will be on headers at a higher force, i.e., headers following a long pass (more than 35m), crosses, corners and free kicks.

· Recommended that a maximum of ten higher force ;headers are carried out in training per week.

· Early evidence suggests heading the ball from a throw reduces the impact force.

· Use of foam ball at given instances in training recommended.

· Encouragement on neck muscle strengthening to reduce impact of force.

The YouTube video attached below further explains the FA’s approach to heading in training:

This guidance is only in regard to training meaning there exists no heading restriction or guidance on actual match play. Importantly, whilst heading is a part of football, there is an option to regulate the force of heading in training. The recommended limit of 10 headers per session is calculated by Opta Data and the use of peak linear acceleration (g) and peak rotational acceleration (rad/s^2) data, in order to determine this optimal level needed to prepare a professional footballer for match scenarios.

With the use of the PFNCC study data, FA Chief Executive Mark Bullingham has released a statement saying, ‘we are introducing, in partnership with the other football bodies, the most comprehensive adult football guidelines anywhere’.

This statement suggests that the FA have taken full responsibility and ownership over the sanctioning of scientific PFNCC data and ultimately, responsibility over their heading guidance, holding them accountable for any relevant negligent activity. The sheer provision of guidelines does not automatically prevent liability and it is these guidelines which must be tested against strongly.

The Duty of Care Owed:

Whilst the aim of this article is not to make a legal claim, it is assumed that should a claim arise, in which footballers were to seek damages for long-term brain damage, it would be a claim against the FA and in the form of a personal injury claim. This is a strong assumption in line with the notorious and analogous personal injury claim arising from 4,500 former (living and deceased) National Football League (NFL) players against the NFL Association itself. The result of the potential lawsuits was a $765Million settlement in which the NFL did not formally accept liability but were still asked to pay the damages. Hence, having established a likely precedent, I would like to focus on who the duty of care is owed by, setting this article out in the style of a personal injury claim.

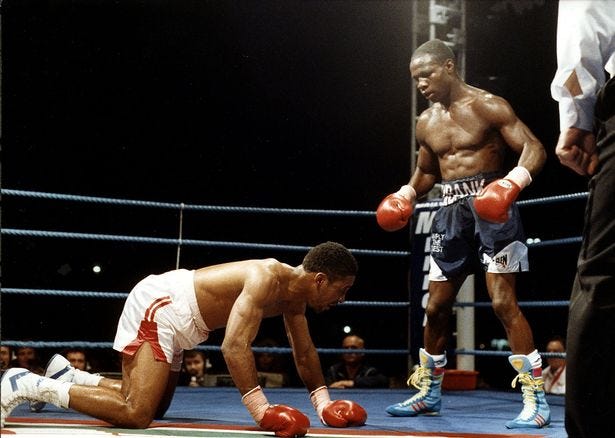

The duty of care is owed by the FA to protect its professional players from brain damage. Historically, precedent has been developed to establish where a duty of care is owed. In this case, it is the duty owed by a professional sports body to its athletes. Whilst a precedent has not been established in football, there seems no real use for the three-stage test set out in Caparo v Dickman 1988 as a means to combat this lack of analogy. This is as Watson v British Boxing Board of Control 2000[ is analogous enough to act as a precedent. What this case did was add an extension to the duty of care owed to professional athletes. Michael Watson fought Chris Eubank for the WBO Middleweight World Title but as the fight was stopped, he suffered from a brain haemorrhage and went unconscious. He was left medically unattended by a doctor for 7 minutes and then sent to a hospital without a neurosurgery unit. In the judgement of the case, it was determined that not only did the BBBC have to take care of any fighting injury but also ensure these injuries were properly treated. This was an extension of the duty of care that was unique to the case and ‘broke new ground’ in negligence claims regarding the welfare of professional athletes.

Hence, the BBBC were responsible for the treatment and protection of a boxer post injury and ensuring the care is there. If we are to apply this to the case of head injury in football, we can infer that the FA are the governing body responsible for the care of players who have suffered from repeated head trauma (average OPTA statistics show an average force of 7928N on Centre-Backs heads per 90 minute match that could lead to brain injury, most commonly, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). This is the equivalent to a human skull facing 7.5 g of force per 90 minutes, which is an abnormally large amount. Hence, there is a responsibility on the FA to provide care to professional footballers, to not only to avoid head injury but also provide care to those who had or were likely to sustain head injury.

In this case, there can be an argument on behalf of any professional footballer who has suffered from depression, CTE, alzeihmers, or any other type of long-term brain damage, to claim a duty was owed to them by the FA. For example, the FA could have provided greater protective measures to reduce repetitive trauma upon their heads through the reduction of heading impact in a controlled environment such as training. The British Medical Journal’s study ‘A systematic review of potential long-term effects of sport-related concussion’, which concluded that there is a link between cognitive impairment, brain-damage and former sports players in contact sports such as football, can be used to highlight the dangers of such impact and the negligent heading guidance the FA have produced (as seen above).

One may argue that there is a defence of consent which eases the duty of care owed by the FA to professional footballer’s, this is the defence of volenti non fit injuria. This defence argues that if one knew the harm, they were putting themselves in, were informed of the risks and ultimately carried through with it, then they had consented to it. Footballer’s, especially in recent times have been made aware of the risks of brain damage after their career has ended, this can be seen through the increased media attention on England’s 1966 World Cup winning squad, in which 5 players have been diagnosed with dementia.

Nobby Stiles, one of these members, died at the age of 78 with dementia. His family used this as a chance to bring to the fore the dangers that ex-footballers are facing beyond their careers. They questioned why the Premier League ‘receives £3bn a year’ and why the FA do not use the ‘tens of millions of pounds available today’ to them. Yet, even with this raised awareness, footballers continue to directly or indirectly consent to the risk. This is as there is pressure on a footballer to maintain a high quality and availability for their team, either out of love for the game or in order to renew or improve on their contract or presumed legacy within football.

Troy Deeney represents one of many footballer’s who have spoken up on their awareness and acceptance of the consequences of long-term head injury in football. Speaking to Talksport, he fully supported player control over their physical state after a head collision instead of it being put into the club Doctor’s hands.

However, given the extension of duty of care created in Watson v BBBC, this defence does not account for the lack of safety provisions made from a governing body to its athletes. As we have laid out, there are guidelines that footballers are provided to follow regarding responsible heading limits throughout their careers, but there is a consistent lack of personal support to the player beyond this. The injuries sustained during a career are the responsibility of the FA and this includes the impact of such injury beyond a career’s end. If the FA continue to provide a guideline that continues to result in brain damage, then they cannot be protected by the defence of consent to this duty owed until the long-term consequences have been eradicated.

Ultimately, the FA have assumed a duty of care upon professional footballers in England by admitting their responsibility over these very guidelines that have aimed to reduce the impact upon a footballer’s brain from youth level to professional level.

Standard, Breach Of Duty & the Complexity of Professional Opinion

Now a duty has been established, we must determine the standard expected upon the FA and whether they have fallen below this standard thus far. As the professional governing body in English Football, the FA would be held to the professional standard established in Bolam v Friern Hospital 1957[, this case established the two-part Bolam Test:

1) Where the defendant purports to have a special skill, they defendant’s conduct is judged to the standard of a reasonable person with such expertise.

The FA should in this case be held to the standard that a reasonable governing body in sport should be held to. This means the responsibility to provide adequate safety guidelines and measures for its professional footballers as a consequence of repetitive head trauma in their careers.

2) If a body of professional opinion has determined the professionals act to be adequate, then, excluding rare instances, the professional will not have fallen below the standard.

Applying this to our case, should the FA’s decision making be defended by a body of professional opinion, then they will not have fallen below the standard of care required. This will be a key talking point of this section.

Once the standard has been set, we must see whether this has been breached by falling below this set standard.

Firstly however, I would like to make this point clear. The FA are not responsible for any breach of duty that is a player’s individual and absolute responsibility. Condon v Basi 1985[ was a case that featured a footballer in the Leamington Local Leagues (the defendant) who was deemed to have recklessly tackled the (claimant) and injured him, resulting in a broken leg. The key question of the case was establishing a standard of care for the footballer. It was concluded that the higher the standard of football, the higher the standard of care would be established regarding recklessness from a footballer. Sir John Donaldson MR said, ‘Thus there will of course be a higher degree of care required of a player in a First Division football match than of a player in a Fourth Division football match.’

Importantly, at the time of the case the first division was a professional division, and the fourth division was non-professional, so we should take it to mean that the professional standard, which is what is of interest in our case, should be held higher than the non-professional standard. Hence, should a head injury be caused out of the recklessness of a professional footballer, then the FA are not negligent for this individual instance. However, as Fulham v Jones 2022 has recently established, the individual recklessness of ‘actual serious foul play’ on an individual’s behalf has an extremely high threshold, meaning that an individual could only be liable for a head injury if their act towards the injury was ‘that endangers the safety of an opponent or uses excessive force or brutality’.If this criteria is not established, the negligence will fall back towards the FA.

We have established that whilst there may be instances of individual player liability, these instances will be rare. The FA provide the guidelines on heading and have a responsibility to look after the wellbeing of its professional footballers as one of their core duties. We can see this in the FA Handbook for the 2022/23 season, section 37B.1 titled ‘Medical Regulations’ in which the FA ask professional clubs to adhere to the medical regulations set out by the FA. This is the assumption of responsibility and medical guidelines that the FA have taken over its professional footballers, representing a professional standard of care.

In the knowledge that the FA have provided their own heading guidelines with the aid of medical professional opinion and evidence from the PFNCC medical and statistical team which assessed the links between heading impact and optimal levels for heading in a regulated training environment. The bodies of professional opinion included:

- University of Central Lancashire’s Performance Hub

- Opta Statistics from Stat Perform

- Sport & Well Being Analytics Limited (SWA)

- PFNCC Sub-Committee featuring a heading working group from all professional FA Leagues.

Consequently, this study and the combined efforts of all the above bodies of professional medical opinion, the FA drew up their heading guidance with restricted heading usage in training. The case De Freitas v O’Brien 1995, was an important case that determined one could establish a ‘body’ of professional opinion even if it was in a minority. In this case 11 medical professionals out of 100 medical professionals were deemed enough of a body of professional opinion. Ultimately, with reference to our case, alongside the PFNCC heading review, the FA signed up to a group of medical findings at the ‘4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012’ which led to an FA approved plan of action regarding head injury management and a concussion protocol for all FA contracted footballers.

This represents a substantial body of opinion that has been incorporated by the FA to better player welfare and prevent long-term head brain damage in footballers. Now, with reference to step 2 of the Bolam test, this would suggest that the FA has not breached its duty to professional footballers by falling below the standard of care. However, there exists many sources of medical opinion that contradicts the use of heading in football by highlighting the detrimental effects of repetitive head trauma. Famously a Norwegian study by Alf Tysvaer and Odd-Vebjørn Storli named ‘Soccer injuries to the brain: ‘A neurologic and electroencephalographic study of active football players’ found some pretty frightening conclusions. It concluded that the average force of impact of a ball onto a head is the equivalent to a boxer being jabbed to the head.

Considering the limit is 10 headers a session in professional training and a professional team train on average 5 times a week, the guidelines permit an allowance equivalent to 50 ‘boxing jabs’ to the head per week. This does not include the force of impact sustained in a match.

Dr Robert Cantu – a leading brain trauma expert, backed up this evidence by raising 13 studies which all demonstrated,

‘that sub-concussive hits in sports . . . have shown abnormalities on DTI MRI, have shown abnormalities on functional MRIs . . . and [have] also [shown] breakdown of the blood-brain barrier . . . . And that’s happened without recognized concussion, just from repetitive trauma’.

Professor Willie Stewart has involved this evidence to come to the conclusion that heading in youth football must be banned. The latest research from Willie Stewart was based on the comparative analysis between 7,676 former Scottish male professionals against 23,000 men from the general population.

From a logical perspective, the evidence cannot be denied, there is more and more research suggesting the dangers of heading in football. He found an ‘association of field position and career length with neurodegenerative disease risk in former professional soccer players’ which suggested defenders are’ 7 times more likely to suffer from dementia than the general public, and that outfield footballers are four times more likely to suffer from brain diseases than the general public.

The problem we are faced with is that such health conditions appear decades beyond a player’s career however, we cannot remain negligent to the clear impact that heading a ball has had on former professional’s health. From a legal perspective, this conflict in medical professional opinion should not be considered an absolute metric to determine whether the FA has fallen below the standard of care by allowing heading to be part of professional training. It would be hard to tell whether a breach of duty has occurred given the FA heading guidance document sanctioning the restricted use of heading in training via scientific and statistical evidence, but equally as Willie Stewart was commissioned by the FA to research into footballer’s brain health and concluded that heading should be eliminated at youth level football, the medical opinion varies.

This matter may only become clear as further evidence filters out either demonstrating that the FA produced a negligent guide that encouraged heading or whether this restricted heading limit effectively reduced the potential for long-term brain damage.

It may be of better use to consider breach factors that could determine whether a standard has been breached. The seriousness of potential harm factor as established in Paris v Stepney Borough Council 1950, should most definitely be of consideration to the FA. Should these new guidelines not benefit footballers by not reducing the instances of brain damage in professional footballers, the evidence as provided by Willie Stewart and numerous further studies on the dangers of repetitive head trauma in football will demonstrate that serious life altering and, in many cases, life ending brain disease will have occurred as a result of the FA’s negligent guidelines no matter whether their guidelines were based on current scientific evidence or not. This is as numerous studies will have also advised against the use of heading in at least youth level football.

There is a natural link to the magnitude of risk at play. The magnitude of risk was first established in the case of Pearson v Lightning 1998 in which it was foreseeable for a golf ball to hit another player. I find given the evidence provided that there is foreseeability on behalf of the FA that if they were to not follow Willie Stewart’s guidance and ban heading at youth level now, the risk to professional footballer’s is that they will increasingly be exposed to a higher proportion risk of brain damage.

I feel the severity and magnitude of head injury will ultimately prove to be a detrimental factor to the FA should personal injury cases in brain damage arise from footballers in the years to come.

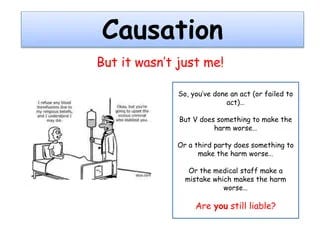

Causation and The Question Of ‘Industry’

We will also need to consider the factor of causation should the FA’s heading guidance ever be questioned to be negligent. Should a breach have been determined, factual and legal causation must also be established to provide a claim in negligence.

Factual causation will provide the main discussion point in this section. This is as legal causation is to be concerned with potential novus actus interveniens that can only really be tested when an actual personal injury claim for head injury in football arises. The main concern for us is whether in a future personal head injury case the ‘but for’ test can be satisfied. This is the test that, ‘but for the FA’s negligent guidelines on heading, would a footballer have suffered long-term brain damage.’ The answer right away is that we are unsure. Due to the extreme time difference between a footballing career and the resulting consequence of long-term brain damage, we cannot prove or provide a definitive chain of causation that would suggest repetitive head trauma experienced from heading is the absolute contributor to the player’s brain damage.

Many other factors could be the case, it would be impossible to argue that the repetitive head trauma from a playing career was the majority and sole reason a footballer ended up with brain damage, this is as it is not only the ball that a head can collide with in football. Many cases of serious brain-damage in football have resulted after a clash of heads between two players. The most famous example in recent times was the collision between Raul Jimenez and David Luiz. Jimenez, the Wolverhampton Wanderers striker clashed heads with Arsenal defender, Luiz. Consequentially, Jimenez fractured his skull and required emergency surgery on his brain to keep him alive before he made a full recovery in the following year. This, like many incidents in life can be seen as an accident and away from the regulations of the game.

Whilst there is evidence for repetitive ‘ball on head’ impact being dangerous in the long term, we cannot measure its percentage responsibility for long-term brain injury in ex-professionals due to the amount of contact a footballer’s head encounters with other body parts and also other playing heads in their career. The weight of an adult head and force a person can produce from an arm, foot or elbow in a playing action towards the heads is significantly more than the weighted force of a football.

A Norwegian study led by Thor Einar Andersen in 2004 looked at 319 fixtures of the 1999/2000 Norwegian Premier League Season. There were 297 acute injuries in which the head was involved. 98% of these head injuries were caused by a head collision with another’s head, elbow, arm or foot. What this suggests is that there are several other kinds of collisions in football that can contribute to a head injury in football and the responsibility does not solely lie with the FA’s heading guidelines regarding repetitive impact. One may argue on the other hand that should the FA sanction a complete ban on heading in professional English football, the likelihood of head injury, whether a ball is involved or not, will naturally go down. Thor E Andersen’s study did pick up on the fact that 58% of duels analysed were heading duels, which would mean a football was indirectly the cause of collision between one’s head and another’s body part and this would not occur with the outlawing of heading. Evidently, it will be extremely hard to pin down the FA guidelines as either the singular or majority reason for why footballers are more likely to sustain brain damage, thus making the FA not negligent as it stands.

This is why I would look to the material increase in risk test as a potential way to find negligence on the FA’s behalf regarding their heading guidance. The material increase in risk test was established in the case of McGhee v National Coal Board (1973) and acts as a representative for cases in which:

1) The ‘but for’ test cannot be established and,

2) When factual causation cannot be proved by the material contribution test that would state ‘on the balance of probabilities, but for a defendants actions the injury would not have occurred’.

Hence, as we have shown thus far, the FA are likely to successfully defend their stance that long-term brain damage in ex-professional footballers cannot be an overwhelming consequence of their guidelines on heading in football and at the very most, a consequence only of the nature of football, in which professionals are aware of the risk that non-ball related head collisions can immediately have on their brain (refer back to the Jimenez and Luiz incident).

What the material increase in risk test aims to do is show that the act of a defendant materially increased the risk. In the case of McGhee, the tortious exposure to dust particles on the claimant’s skin was materially increased the longer the claimant was exposed to the dust. In our case, the fact that the FA allow the use of heading a football from the earliest of youth levels all the way to the professional level means that they have allowed for the material risk of long-term brain damage with the extension of time a player can head a football. Many studies have requested the ban of heading at youth level, including the previously mentioned Willie Stewart study sanctioned by the FA in 2017. So, it may be easier to prove that repetitive head trauma through heading a ball in training and matches will increase the chances of a footballer to suffer from long-term brain damage in the future.

The problem we may come across with this is that the material increase in risk test is limited to industrial disease cases only, in which there is scientific uncertainty over a cause. This is as it would be far too easy to use the test in a general sense regarding all kinds of tortious acts. All that would be required is a reason as to why one act is tortious. So, the dilemma for those potentially making a claim against the FA is to try to prove that football is an industry in which the science of potential long-term brain trauma remains unclear.

The oxford dictionary defines an industry as ‘a particular form or branch of economic or commercial activity.’ In this sense, we could argue football may be an industry as whilst it is a sport, the commercial success and economic benefit resulting from it cannot be questioned. More specifically to our case, the FA not only acts as the governing body of English football but also as a business which manages the English game. In the 2021/22 season, the FA Limited achieved profits of £132m as a result of their activities in English football. So quite literally, we could consider it an industry.

With the studies mentioned in this article which highlight the link between football professionals and long-term brain injury, I believe it would not be a stretch for one to argue that brain diseases such as dementia are an industrial disease applied within the industry of football.

Where do we go from here?

On the face of it, there is increasing evidence to suggest a causal link between long-term brain damage and repetitive head trauma as a professional footballer. The FA may look to new approaches to protect the young brain and also themselves from negligence. They have implemented a trial to remove deliberate heading at under-12 level for the 2022-23 season. This suggests to me that they fear negligence and genuine fault on their behalf regarding their heading guidance released the season before.

Quite simply, the risks of long-term brain damage, such as CTE are far too severe to be neglected and the impact of such damage to footballers may spiral out of control and directly impact a larger population of innocent parties. The devastating case of Aaron Hernandez acts as a warning to all. As a 27 year old former NFL athlete, he suffered from CTE due to repetitive head trauma, ultimately this contributed to not only his own homicide but the murder of his dear friend Odin Lloyd.

Despite the overwhelming evidence suggesting repetitive head trauma from the world of sport leads to serious long-term brain disease, the FA within their new guidance continue to allow for repetitive head contact to occur in football and should tighter restrictions not occur on these guidelines given the scientific evidence, the FA will likely find themselves negligent for any future brain damage claims that may occur against them in their handling of footballers during and beyond their career.

I would like to clarify that for the purposes of the article I focused upon the English game and governing board when making reference to head trauma and legislation. However, make no mistake about it, the neglect of head trauma is prominent across the global game. The recent World Cup has provided frightening reminders of this. Most notably in the England vs Iran fixture, Iran’s goalkeeper Ali Beiranvand, despite being quite clearly out of it, shockingly continued to play for a few further minutes beyond the restart of the game. It pains me to say but I am now forced to ask myself, you and the world of football these questions.

When will football wake up to this reality? I fear only in the wake of a current and recognisable death caused due to medical and general negligence.

Does football have to ban heading all together? Maybe.

Will this ruin a vital aspect of the game and consequentially an essence of the game, football, itself? Most likely.

Will a ban save lives? Without a doubt, yes.

Ömer Çayir

Co-Founder

Editor-In-Chief

Revamp The Game

TABLE OF LEGAL CASES

Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 W.L.R. 582 (26 February 1957)

Caparo Industries pIc v Dickman & Ors [1990] UKHL 2 (08 February 1990)

Condon v Basi [1985] EWCA Civ 12 (30 Apr 1985)

De Freitas v O’Brian [1995] PIQR 281

Fulham v Jones [2022] EWHC 1108 (QB)

Paris v Stepney Borough Council [19510 1 All ER 42, HL

Pearson v. Lightning (1998) 95(20) LSG 33

McGhee v National Coal Board [1972],UKH1 7 1 W.L.R. 1

Watson v British Boxing Board of Control [2001] QB 1134, EWCA Civ 2116

Bibliography

Albert, Angeline ‘Headers must be banned as footballers are more likely to die of dementia’ (2021), <https://www.carehome.co.uk/news/article.cfm/id/1654478/Headers-must-banned-as-footballers>

Andersen, Thor Einan ‘Mechanisms of head injuries in elite football’ (2004), 38(6), 690-696

Cover Three, ‘Kids Brain Development: The factors and Stages that shape Kids brains’, https://coverthree.com/blogs/research/kids-brain-development

Duru, Jeremi ‘No Hands…And No Heads: An Argument To End Heading In Soccer At All Levels’, (2019) https://www.lawinsport.com/topics/item/no-hands-and-no-heads-an-argument-to-end-heading-in-soccer-at-all-levels#sdfootnote15anc

England Football, ‘Adult Heading Guidance’, (August 2021) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bicDwvSMM1I&t=115s

Football Association, English Football introduces new guidance for heading ahead of 2021-22 season, (PDF FA-Heading-Guidance) < file:///Users/omercayir/Downloads/the-fa-heading-guidance.pdf>

Football Association ‘The FA to trial the removal of heading in u12 matches and below in 2022-23 season’ (2022) <https://www.thefa.com/news/2022/jul/18/statement-heading-trial-u12-games-20221807?

Football Association, ‘2022/23 Handbook, ‘Section 37, Medical Regulations’’, (37-MEDICAL-REGULATIONS.PDF) file:///Users/omercayir/Downloads/37-medical-regulations.pdf

Gallagher, Danny ‘It's all a blur': Wolves striker Raul Jimenez reveals he CAN'T REMEMBER the moment of his horror head injury, has struggled to walk and had to be fed breakfast in bed by his girlfriend while recovering as he finally nears a return’, (2020) <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-9277803/Wolves-striker-Raul-Jimenez-struggled-walk-eat-David-Luiz-clash-heads.html>

Gardner, Manley G., AJ, Schneider KJ, et al, ‘A systematic review of potential long-term effects of sport-related concussion’ British Journal of Sports Medicine (2017); 51:969-977.

Magowan, Alistair ‘Nobby Stiles’ Family Says Football ‘Must address the scandal of dementia’ (2020), <https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/54976910>

Oxford Dictionary ‘Industry Definition’ https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/american_english/industry#:~:text=noun-,noun,is%20mostly%20used%20in%20industry.

Reid, Alex ‘Troy Deeney Receives Huge Amount Of Criticism For ‘Dangerous’ Comments About Concussion’ (2020), <https://www.sportbible.com/football/football-news-troy-deeney-criticised-for-dangerous-comments-about-concussion-20201130>

The Guardian ‘New images show Aaron Hernandez suffered from extreme case of CTE’ (2017) https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/nov/09/aaron-hernandez-cte-brain-damage-photos

The Guardian, NFL Concussion Lawsuits Explained, (2013) https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2013/aug/29/nfl-concussions-lawsuit-explained

Tysvaer, Alf and Odd-Vebjørn Storli, ‘Soccer injuries to the brain: ‘A neurologic and electroencephalographic study of active football players’ (1991), Vol 17, issue 4, 573-578